by Nat Winn

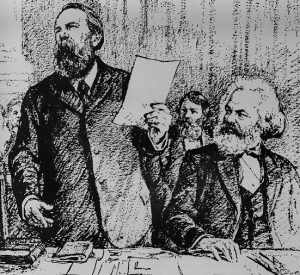

Since the creation of what Engels referred to as scientific socialism by Marx and Engels over 175 years ago, we have that much concrete practice to tell us what works and doesn’t work. To refer and draw lessons from that practice is not abstraction, it is concrete method for developing real strategy.

We should not think that our limited individual or local practice will lead us to direct answers about revolutionary strategy or change. We should look at practice as social practice and most of what we will learn from is in fact indirect experience, tying together experiences over time and geographical space. Again this is not at the level of abstraction, it is an argument for how we arrive at correct strategies.

For instance revolutions are not made from the bottom up. They happen at the heights of power and involve the forcible overthrow of one existing coalition of social forces by a new coalition of social forces and qualitative changes in the societal system of ownership, and in social relations. Revolutions involve significant minorities of society, but enough of a social force and enough of the rest of society fed up enough to at least not support the ruling powers, to make the old ways of governing not work anymore.

This would mean that revolutions emerge from different sections of society, from the bottom up, from the emergence of shifting social coalitions – but – they are made at the heights, when the old rulers are forcibly overthrown by a new group of social forces representing new ideas and solutions for existing social crisis.

Revolutions made successfully in the 20th century also demonstrate that revolutionary movements may begin with some degree of decentralization and hopes of radical democracy, however, in order to do things like defend themselves against counter revolution and to organize new social relations and and an economy, there usually is a need for a tightening up, and more centralized forms of organization. This does not mean the absence of decentralization, but there is a relationship between localized or decentralized inputs and more central planning and organization.

There are a few points to be made to summarize what is being argued.

One, localized practice needs to be gathered and summarized at higher more centralized levels to develop real strategy. Most of the lessons we learn will be learned from indirect experience.

Two, it is not a question of socialism from the bottom up or from the top down. Revolutions happen at the heights of power where the old rulers are forcibly overthrown. At the same time they involve social forces from different sections of society and would not be worth their salt if they do not involve real solutions and involvement for and from the most marginalized and oppressed in society. It is socialism from the bottom and at the heights.

Three, it is not a question of centralized or decentralized power. Form always follow function and never vice versa. We will need both centralized forms of organization and more decentralized inputs and new relations in the workplace and communities that mark the transition to classless egalitarian society.

These are lessons drawn from social practice and they are concrete lessons learned collectively over the past 175 plus years and more.

There is more to say about this, including why summing up the experiences of attempts to build socialism after successful revolutions in the 20th century and not dismissing them as state run or authoritarian is quite important if we are to get where we need to get.

For now this clarity about the need to learn from concrete social practice, not merely our own localized practice, and its distinction from abstraction, is a necessary point to argue for.