Whenever people seek a way out of their oppression, whenever they launch themselves into intense struggle, they start to seek out a philosophy that can guide their path.

From the earliest days of modern capitalism and its gravedigger, communist revolution, the name Karl Marx appeared prominently in both revolutionary theory and in the intense, global attempts to seize power and create a new liberated, socialist society.

Meanwhile, important questions have arisen, over and over, in our attempts to understand and apply Marxism — including the issues raised in this two-part series.

- Which Marxism are we seeking to apply?

- Is communist theory an ongoing creative process — built on crucial insights of Karl Marx, but incorporating subsequent lessons and insights?

- Or is there some pre-distilled, finalized Marxist doctrine and set of principles laid down, fixed and complete, in our own past?

- Are we required to simply identify and adopt some specific inherited form of Marxism?

- Or will each new revolutionary advance necessarily require both affirmation and rupture with our own previous communist understandings?

The Partisans is sharing a two-part series focused on these questions:

· Part 1: Marxism is not a Layer Cake

· Part 2: Marxism Is More Like a Bush in an Ecosystem

By Mike Ely

If you teach scientific ideas in a religious way, you have not taught science, you have taught religion. If you gather up buckets of “true facts” and teach them in a rote and dogmatic way, you have not taught truth, you have taught rote and dogma.

There is a great wealth of insight and experience embodied in the past revolutionary attempts — both in their theoretical work and their actual practice. It is extremely important to dig deeply into it, to become familiar with the history and theory of 19th and 20th century communist movements.

But the approach that turns a core set of such writings into “classics” is the teaching of religion and not creative materialist thinking. And in the end it makes it impossible to learn many of the things we need to learn.

There is great power and precious material within the body of international Marxist theory and method — but if we treat it like an encapsulated and semi-finished doctrine we will be depriving ourselves of that power, and circulating dead verdicts out of space and time, drained of precisely the creative analytical approaches that Marx pioneered, and that Lenin and Mao advanced to lead revolutions.

For that reason it was valuable to raise that remark from Lenin:

“People for the most part (99 percent of the bourgeoisie, 98 percent of the liquidators, about 60‑70 percent of the Bolsheviks) don’t know how to think, they only learn words by heart.”

Badly Aging Orthodoxies

Let’s dissect the features of the too-familiar and common approach we are critiquing:

1) Teaching that we can take the “classic” works as simple truth — consume and then apply them with confidence that they are more-or-less universally relevant and correct.

There was an early debate in the Revolutionary Union:

“Is our common line the material contained in our own evolving organizational documents (Red Papers and so on), or is everything contained in Marx, Lenin and Mao also part of our basis of unity?”

And the second argument represents a certain view of Marxism-Leninism, i.e. that the theory we need exists (was created and fleshed out half a century ago) and that what we need to do is mainly assimilate it and apply it. And that whatever Lenin or Mao said is simply true, and it can be taken as true.

You see that thinking all the time, when someone quotes Lenin and assumes that because that quote said it we can proceed (in our discussion and logic) as if the point has been made and proven. (“The Bible says it, i believe it, and that’s that.”) In fact, there is value in examining what people like Lenin said and wrote on a topic. But when we do, we have the burden to show that what they said applies now (and even sometimes that it was true then) — or at least to so structure our argument and logic that we do not assume (or train others to assume) that it is simply and universally true.

I think the simplicity of Stalin’s logic is deceptive — because reality is not like that. And when Stalin implies (over and over) that the truth is obvious if you just have the right motivation and honesty, and breaks it down with famous simplicity (“and hence….”) But this was actually a method that distorted reality. It was a bootcamp for the reduction of Marxist methodology.

Much of the “reductionism” and theoretical poverty of modern communism is entwined with the training of Stalin-era Marxism (and before it mechanical currents in European Social-Democracy generally). In Stalin’s case (from Foundations of Leninism on) the theory was far more about codifying a state-legitimizing doctrine than the exercise of a materialist exploratory scientific analysis of reality. There was a popularization of Marxism — but often it was undermined as a critical and creative analysis, and affirmed as a set of state-approved orthodoxies.

In the 9 Letters we wrote:

“… since Mao died in 1976, this Maoist movement has not been a fertile nursery of daring analyses and concepts. A mud streak has run through it. Even its best forces often cling to legitimizing orthodoxies, icons, and formulations. The popularization of largely-correct verdicts often replaces the high road of scientific theory — allowing Marxism itself to appear pat, simple and complete. Dogmatic thinking nurtures both self-delusion and triumphalism. In the name of taking established truths to the people, revolutionary communists have often cut themselves off from the new facts and creative thinking of our times.”

I repeat what we said then:

“We need to break with that fiercely, and seek out the others who agree.”

We should not uphold or continue Stalin’s simple and pat approach to Marxism.

And we should not uphold Stalin’s History of the Communist Party — on the contrary we should study it as a negative example of “cutting the toes to fit the shoes” and of “reading history backwards” so that events are all tidy, clear, predictable. It is an exercise in mechanical thinking — “This was this, that was that” — the events described are heroic and world historic, but it is done with a mechanical worldview that departs constantly from real history or materialist dialectics or the workings of real revolution. It is a book that has mythologized a very particular approach to revolutionary preparation — in ways that led whole generations of revolutionaries around in circles.

That kind of doctrinal orthodoxy is attractive, even seductive, especially for new people who find the completeness breathtaking. The problem is that it is a deception — it is not, in fact, there. The coherence is a deception. Much that is presented as science is not actually scientific. Much that is presented as coherent is in fact (quite naturally) woolly and contradictory.

Did Lenin make mistakes? For me, that isn’t even the question. Sure, everyone makes errors, and obviously that includes Lenin.

But what is more profound is the question of the overall skein of Bolshevik theory and practice. What can we learn and adopt from them, and meanwhile what currents in their thinking should we look at more critically?

Avakian says the Bolsheviks had a kind of pragmatic instrumentalism that jumped out at various points — including during the Red Terror. I think Avakian is wrong on some of that — and that it is an example of where Avakian has a detached and idealist incomprehension of what politics and class struggle for power actually (of necessity) looks like.

Meanwhile, others have raised whether there was too much “theory of the productive forces” in the whole Russian movement (Soviets plus electrification = Communism), so that their very radical revolution far too easily flipped over into a massive two decade effort focused on industrialization and modernization.

In any case, we need that kind of sweeping assessment of the Bolshevik problematic (not just an “overall defense of Lenin, while identifying Lenin’s particular and occasional errors.”) Anyone writing in the early 20th century wrote and acted in ways deeply marked by their times and assumptions.

Theory (even the theory of our best revolutionaries) isn’t like raisin bread with wonderful white stuff and a few pesky raisin “errors” stuck in randomly. In a sweeping way, Lenin led the first socialist revolution and led important revolutionary ruptures and advances — but there is a need to take an overall look at the whole Bolshevik problematic (its assumptions and characteristics) in a way the helps us construct an approach for the revolutions a century later.

2) Assuming that these works don’t contradict themselves or each other.

There was an early debate in the New Communist Movement over whether Marxism was like a layer cake, i.e. Marx and Engels laid down the first layer, then Lenin built on that, then Stalin built on that, then Mao built on that.

And you got a vision of a “development” of theory that had little dynamic contradiction — and where the new did not actually emerge from the internal contradictions of the old.

Why was something new, like Leninism, necessary after 1914? In some people’s view, it is not because there were any contradictions within previous Marxism (including gaps, flaws, misjudgements, wrong steps), but simply because new conditions and new phenomena had emerged: imperialism, the first socialist revolution, monopoly capitalism replacing competitive capitalism.

So Leninism was seen as (first) an affirmation and (then) a needed development of Marx’s work (but without any real negation).

Leninism was (in those conceptions) the Marxism of the new era of imperialism and proletarian revolution. And so, problem solved: you needed a new leap because there were new problems. And you did not have to acknowledge that our theory needed (like all theory) to be self-critical, that it needed to step back sometimes and take a new direction. That there were whole parts of it that needed to be changed (not just updated but also just changed).

This is the analysis made in Stalin’s Foundations of Leninism.

And forty years later, this produced (for the dogmatically inclined) a real problem when it became clear that Mao had come up with a number of radical new developments.

“Can we declare a leap to Maoism if there is not a new era?”

It is virtually a theological problem (like contemplating the paradoxes of the Trinity). To declare a leap without an era is to imply weaknesses and incompleteness in the previous theory! It is to imply development through partial negation! And that was deeply disturbing for some people.

In revolutionary China, there was an attempt to solve this theological problem by trying to declare that there was (in fact) a new epoch, and Mao’s work was its new “ism.” At the Ninth Party Congress, Lin Biao declared:

“Mao Tsetung Thought is Marxism-Leninism of the era in which imperialism is heading for total collapse and socialism is advancing to world-wide victory.”

The only problem was, of course, that it wasn’t true.

There was not a new era in that sense. Imperialism was not “heading for total collapse.” And (more important) the only way you could see socialism as advancing to worldwide victory is to view the Soviet bloc as semi-socialist — and so Lin Biao was smuggling a negation of Mao’s theory into his most public declaration of Mao Tsetung Thought.

Far into the 1980s and 1990s, some Maoists refused to talk about Maoism because of this issue — because the very use of the word “Maoism” meant that there was a leap beyond Leninism without a new era, and what could that mean but a critique and demotion of Stalin?

And in fact Mao’s theoretical developments involved precisely critique, partial negation and demotion of Stalin.

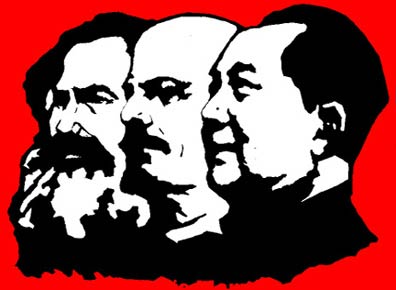

Those who upheld Marxism-Leninism-Maoism often tended to portray the “three heads” (of Marx, Lenin and Mao), while many of those clinging to other formulations (of Marxism Leninism, or Marxism-Leninism Mao Tsetung Thought), tended to put forward the “five heads” (where Engels and Stalin are on equal footing in the pantheon). And some used both, eclectically.

The development of theory and the critical examination of past theory can be agonizing (and even outrageous) to those who want each of the “classic” theorists to be assumed “correct”, and want each generation of Marxism to be a non-interacting sediment — like a distinctly layered cake which develops through new applications, but does not significantly self-negate.

In an earlier discussion (following The Predicament of Inherited Maoism) in which I wrote:

“…all our views and verdicts divide into two and will fray over time. And like all correct insights their correctness will often become more relative the farther you get from the conditions and times where they were developed.”

In response Nat W wrote:

“This statement I think is generally correct, however, it poses a few questions I have about the project of reconception. I’ll start by analogy. Darwin developed the theory of evolution and since then, despite some need for correction or slight modification, it has continued to be held by biologists and other scientists as generally correct. Now it maybe true that many years down the line as human knowledge and technology advance it maybe that our understanding of evolution or natural or development as such ceases to be best explained the theory of evolution of species through natural selection. As for now however, it is the best working theory that scientists have in order to understand and impact this given phenomena.”

In fact, Darwin’s theory has been modified in very basic ways. It did not survive intact “as for now.”

Examples: Darwin did not know about genes and he thought that acquired traits could be passed on. The development of genetics (from the 1920s to the 1930s especially) required a huge leap in evolutionary theory — incorporating genetics in a structural way. (And let’s not forget: the doctrinal conservatism of that era’s Marxist-Leninists led them to reject and denounce that leap in evolutionary theory. They had become quite doctrinally conservative and even fearful.)

In that process no one discarded Darwin, no scientist disrespected him. But there was a profound change in key parts of his theory. And even on his most durable contribution (the theory of natural selection) there has been major controversy and change — just for example on the question of “what level does selection happen at?” — some argue it is selection at the level of genes, some at the level of individuals, Gould argues that it is at multiple levels — individual selection and species selection. This is a major revision of Darwin, by someone seen as one of Darwin’s greatest fans.

In fact our communist use of the word “synthesis” is related to the creation of a modern scientific sythesis in evolutionary biology.

Nat goes on to say that key Marxist concepts should (like Darwin’s theory) be taken as essentially true:

“I think that the materialist conception of history and the labor theory of value are similar theories developed by Marx for understanding the development of societies, that for revolutionaries are the best working paradigms we now have for transforming societies in a more just, collective, and egalitarian way. Now these theories are highly contested (as is evolution in mainstream culture), being a key component of the class struggle, another working theory of Marxist revolutionaries that I have seen Kasama contributors and moderators firmly uphold.”

This is an important argument Nat is making, and I want to inject a question:

“Which materialist conception of history? Which one?”

Because if you look over the body of Marxism and communist theory, there is not a pat (commonly appreciated) “materialist conception of history” — but sharply contending and different approaches, in which people have drawn and assumed very different things “in Marx.”

In other words, it is not a matter of throwing everything “up for grabs” (and still less of “throwing away the baby with the bathwater”). But of actually recognizing the state of our theory and the tasks that lie at hand.

Jean Luc Godard’s Omar opens the Nine Letters by saying that the crisis in the communist movement:

“…has given us the right to make a precise accounting of what we possess, to call by their correct names both our riches and our predicament, to think and argue out loud about our problems, and to engage in the rigors of real research.”

3) Not wanting to see communist theory as an evolving, fluid and contradictory synthesis.

I mention all this tortured history (arguing over the name of our “ism”) to draw out how stubborn dogmatism has been and how the existence of doctrine had injected the culture of theology.

Some people made Marxism (and Marxism-Leninism, and MLM) into something like a series of prophecies that build on each other in a revelatory way. (Elijah spoke of the coming of John the Baptist who announced the coming of the Messiah.)

In fact, life, science and our theory is far more messy than that. Marxism is not a layer cake.

Our communist theory has throughout its history both discarded and assimilated. There are no layers, sitting there distinct, separated only by a little frosting and supporting each other bravely as the stack rises.

Marxism has always changed its approach when there was new evidence and phenomena, but it has also sometimes changed its approach simply because the previous one was wrong. And unfortunately the available history of Marxism has obscured that.

Furthermore, communist theory is not “one thing” — it is not one coherent doctrine being occasionally nipped here and refined there. It is (and always has been) a complex of contradictory and often contending investigations — with gaps and dead zones amid vibrant brilliant insights. It is far less coherent than it is presented.

Example: Just try to unravel a Marxist theory of crisis — at any point in Marxism’s history — and you will realize that there is, in fact, no theory of crisis. And examine the pretenders to that throne (Comintern General Crisis theory, or Mandelian long wave crisis theory, or Avakian-Lotta spiral conjuncture theory) — and you will see that there is little continuity or power in any of them. And people keep trying to develop a communist understanding of capitalist crisis, and we should! But we should not pretend or claim that we have it all tamped down — “there for the taking.”

Avakian (back when he was a creative thinker and engaged with the world around him) came up with an important point when he discussed our communist theory as “a synthesis.” It was an important break from those who approached it as a slowly expanding blob of uncontradictory doctrine. At the time, Avakian called for “taking a Marxist view of Marxism.” These were the long ago days of the 1980 essay Conquer The World.

And if you take the view of communist theory as a synthesis — and I think we should — it doesn’t make sense to use a layer cake name. The very name Marxism-Leninism-Maoism-NextGuyism internalizes a whole set of assumptions about how communist theory develops. And also assumptions about how tidy the synthesis process is and how we can/should exclude all kinds of works and thinkers and currents from the inquiry and the canon.

I view myself as a Marxist, a Leninist and a Maoist (as is well known and documented). But I don’t think the decision of the Communist Party of Peru (Shining Path) to adopt a new label of “Marxism-Leninism-Maoism” was an incorrect one. And I don’t think the Revolutionary Internationalist Movement was correct in adopting Gonzalo’s formulation under pressure. Avakian and the RCP had a different proposal in Conquer the World. But they went along because of the politics of the International Communist Movement after the emergence of the Shining Path. (After all, formulations are not themselves matters of principle.)

This adoption of the term MLM repeated (and implicitly) continued the adoption of Marxism-Leninism as a term in the 1920s – and uncritically adopted the process of codification (within the Comintern) which has been quite suffocating for the needed theoretical exploration.

I think we should call our developing evolving contradictory synthesis “communist theory” — and stop promoting a very mechanical heads-in-profile.

Again, it is not as if the doctrine just exists — and we either “uphold it” or “deviate” from it. (A framework that brings Catholic assumptions into communist discussion.) It is a religious approach that assumes finalized revelation and dangerous heresy.

No. Our theory is a large sprawling and contradictory body of inquiry — and it is constantly developing and decomposing. It is encountering new problems, and showing its seams and strains. It is borrowing from nearby thinkers and inquiries (philosophy, economics, science, gender studies, etc.) — just as Marx, Engels and Lenin borrowed actively (and openly!) from the advancing thinkers of their time.

In fact Lenin chose to both affirm and negate significant verdicts in previous Marxism — and he chose to pose as simply the defender of orthodox Marxism against “revisionism.”

And (in fact) Mao’s major new developments of communist theory came on the basis of major critical summations of the Soviet experience (and some very deep criticisms of Stalin’s work in both theory and practice), and when the break came, Mao chose to portray himself as a critical defender of Stalin’s legacy against the Krushchevite revisionists who were seeking to negate Stalin completely.

But in fact Marxism is not a layer cake. Each body of theory is highly contradictory and fluid. And the attempt to apply and develop communist theory in different times and places produces a real need for creative thinking (for both affirmation and negation of previous theory). And all this is very upsetting for the religiously inclined.

4) Looking at Marxism in an encapsulated way.

If you think only five men developed Marxism, then there are a number of things that follow: You call your ideology after those men. You look to your current candidates for that kind of development. You adopt a certain encapsulation of the theoretical and practical process (that assumes a one-to-many relationship between the party leadership and the rest of the world).

In fact, Marxism is the product of a great many minds. And many currents of modern Marxism have (unfortunately) been reluctant to engage and assimilate new ideas (in the way Marx, Engels and Lenin did with great energy).

It is not true that for every topic (the national question, art and culture, organization) we have a tidy set of answers in our ML grab bag. To tell people we do is a lie. To lead people in that way will move away from the actual road they need to take.

There is (in fact) a lot of NEW work that needs to be done. Tons of it. Exciting, invigorating, NEW work that is being dumped in the lap of a new generation. Work! Research, thinking, new analysis, exploration, debate, synthesis, summation! Just look at the work that needs doing in regard to the theory, analysis and practice around Black people’s oppression and liberation.

It was already bizarre and mind-numbing in the 1960s that some people wanted to suckle on creaky aging 1930s Comintern documents — but it is infinitely more bizarre to try it again fifty years later. (People should be familiar with those analyses, of course, but not go there to drink as if it will quench your thirst.)

On such topics we need a great opening and regrouping — we need to cast the net (both widely and critically), and have a fresh start.

And if we were to confine ourselves to the inherited doctrines, and if we were to study them uncritically — we would be rendering ourselves sterile, and mute, and uninteresting.

Creative Reconception not Orthodoxy

Mao said: “study critically, test independently”

We need to approach theory as a critical and creative process — because only that kind of theory can be communist and a guide to action. We need to have a method of study that encourages debate and critical appraisal.

We need to study a wide array of different and opposing views — including by non-Marxists who have insights and influence. We need to study those we disagree with, and we need to study them both to explore those disagreements, but also to learn about the weaknesses in our own previous understandings.

And we need (in ways I have just touched on) to have a theoretical process that is aimed at teaching ourselves and others how to think deeply about the world — “to know things to change things.” That requires something different from the assertion of a doctrine and the development of indoctrination.

In short our theoretical work and study needs to start with the world, with material reality, its contradictions and developments, and we need to investigate how communist and revolutionary thinkers have explored those contradictions and challenged-or-affirmed previous understandings, and we need to approach that process in a way that contributes to making the communist revolution (including by identifying and developing those insights that make such revolution possible).

Originally written for the Kasama Project in 2010.

https://mikeely.wordpress.com/2010/07/13/marxism-is-not-a-layer-cake/